THE DEAD CHICK

THE DEAD CHICK

NOTE: I’m going to be talking unromantically and uneuphemistically about sex here, and ranting a bit. If you’re under 18, there are people who will think you shouldn’t read this. Please consult your own conscience and tolerence levels.

Okay. Here we go.

I have a problem with the end of The Big Book.

There was a lot to like here. The historical writing was particularly luscious. There are passages I want to shove under the nose of a number of authors I could name and say “See? See? Here. THIS is how you write about women and their friendships. This. Right here.” In parts there is a de-romanticization of the way men see women, that famous “male gaze” that is interesting, worthwhile and highly self-aware.

Then we get to the end, and what happens?

Wait for it…

I don’t expect a whole lot of people to read this book, if they can find it, but because this is the internet, I’m going to do this anyway.

SPOILER ALERT!

Okay? Okay. Oh, BTW, there’s also a rant coming.

Okay? Okay.

So, we get to the end, and what happens?…wait for it…In this time-looping book where we slip from present to past, between points of view and narrative styles and complexity, we get the most prosaic possible ending for the heroine. That’s right. The modern girl dies.

Why does she die? Because that’s what happens to abused women. Everybody knows that. Take a look down the line in movies and literature. When nobody can save them, they die.

Oh, it’s all terribly tragic. Just like that masterpiece of modern feminism, Thelma and Louise. This brilliant young woman is so unable to overcome the abuse inflicted on her by her father, and the exploitation of her professor, etc., that despite her brilliance and the discovery of genuinely good people in her life, and getting to be in the place she’s always wanted to be and meeting the kinds of people she’s always wanted to meet, she kills herself. Why? Well…because she does. It’s the tragedy of it, isn’t it? She was abused and she killed herself. That’s what happens, right?

And the author really piled it on. He made it very clear that this was in the end no garden variety abuse, and that, of course it wasn’t her fault, she was so traumatized, etc., she just kept seeking out situations where she was going to be abused. You know, it was one of those long, drawn out suicides.

For the record, I am very, very aware that exploited women do kill themselves. But you know what? They also don’t kill themselves. They suffer and they die, but they also suffer and live. Kind of a lot. But you wouldn’t know it from literature.

I am so, so, SO sick of the dead chick ending. It is not a new statement. It goes back centuries. Woman has a voluntary or involuntary sexual experience that is not within the codified bounds, and BOOM! Gotta die. Either because deviating from the strict code of conduct set by society has got to be seen as suicidal, or because it’s so, terribly, terribly, terribly tragic.

Oh, if she gets pregnant, maybe she gets to live for the baby’s sake, but living just because she wants to live? Not so much.

Maybe it was worth is when Thomas Hardy was writing Tess of d’Ubervilles, but in the 21st it’s cheap tragedy, right up there on the level with a story where the Big Surprise is that the hero’s gay. It’s also obvious tragedy. It’s easy. Of course she dies, because it was all. So. Horrible.

I’ll tell you something else — killing the victim it is NOT a feminist or feminist-ally statement. You know what would be? If the victim lived. If she survived what had happened and somehow managed to heal, even a little, without having to go through being pregnant for the privilege. If the exploitative professor was forced to confront the living woman, rather than just the corpse. THAT would be a profound statement.

Or if he died instead. You’ll notice the man never dies in these scenarios. He never kills himself because he can’t handle what he’s done or what he’s learned. Ever wonder why the woman is always the one who’s got to die?

With all that was new and wonderful and beautifully written in this book about survival, and history and faith, about ways to fight and ways to cope, and the beauty of the world and THIS is the best this character we’ve spent over a thousand friggin’ pages with gets? A bland, dull, worn out repetition of one of the oldest and most worn out tragedies. So sad. Next.

Close the Big Book on a sour note.

I loved this book. Flat out. Had me at hello.

I loved this book. Flat out. Had me at hello. During the Age of Empire, a particular sub-genre of thriller/horror stories emerged in English letters. It involved English travellers finding out that the natives of whatever country they were tramping through might not actually like them.

During the Age of Empire, a particular sub-genre of thriller/horror stories emerged in English letters. It involved English travellers finding out that the natives of whatever country they were tramping through might not actually like them.

THE DEAD CHICK

THE DEAD CHICK

NO MORE TIME TRAVEL THAN STRICTLY NECESSARY PLEASE

NO MORE TIME TRAVEL THAN STRICTLY NECESSARY PLEASE FRIENDSHIP

FRIENDSHIP I belong to the Subculture of the Book. In my culture, books are not just containers for words, they are prizes, trophies, and they come with bragging rights. I have had whole conversations with friends about how many books we own, how many new bookshelves we’ve had to buy; the problem of trying to squeeze one more bookshelf into a small house or apartment; how many individual volumes we own and whether they’re double stacked on those shelves. We bemoan the difficulties of book storage and management in that particular way that is really kind of closer to bragging than actual regret. And we always buy more books. The size of your To Be Read pile is a big part of the Subculture of the Book.

I belong to the Subculture of the Book. In my culture, books are not just containers for words, they are prizes, trophies, and they come with bragging rights. I have had whole conversations with friends about how many books we own, how many new bookshelves we’ve had to buy; the problem of trying to squeeze one more bookshelf into a small house or apartment; how many individual volumes we own and whether they’re double stacked on those shelves. We bemoan the difficulties of book storage and management in that particular way that is really kind of closer to bragging than actual regret. And we always buy more books. The size of your To Be Read pile is a big part of the Subculture of the Book. I’m reading a Big Book. Seriously. This thing is big. Douglas-Adams-space-metaphor-level big. Over 1300 pages long.

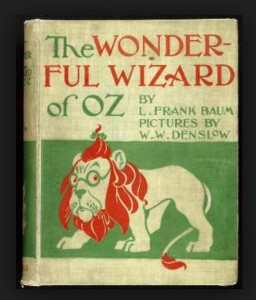

I’m reading a Big Book. Seriously. This thing is big. Douglas-Adams-space-metaphor-level big. Over 1300 pages long. I am an Oz geek. I am not ashamed to admit it. I quite literally grew up on the Oz books. I learned to read out of The Wizard of Oz. I had a babysitter, the teenage daughter of family friends, who had a bunch of the Baum sequels and whenever she came over to sit, or we went to their house to visit, those books were open. When she went away to college, she gave them to me, and I still have them. I’m now reading them to my son.

I am an Oz geek. I am not ashamed to admit it. I quite literally grew up on the Oz books. I learned to read out of The Wizard of Oz. I had a babysitter, the teenage daughter of family friends, who had a bunch of the Baum sequels and whenever she came over to sit, or we went to their house to visit, those books were open. When she went away to college, she gave them to me, and I still have them. I’m now reading them to my son.