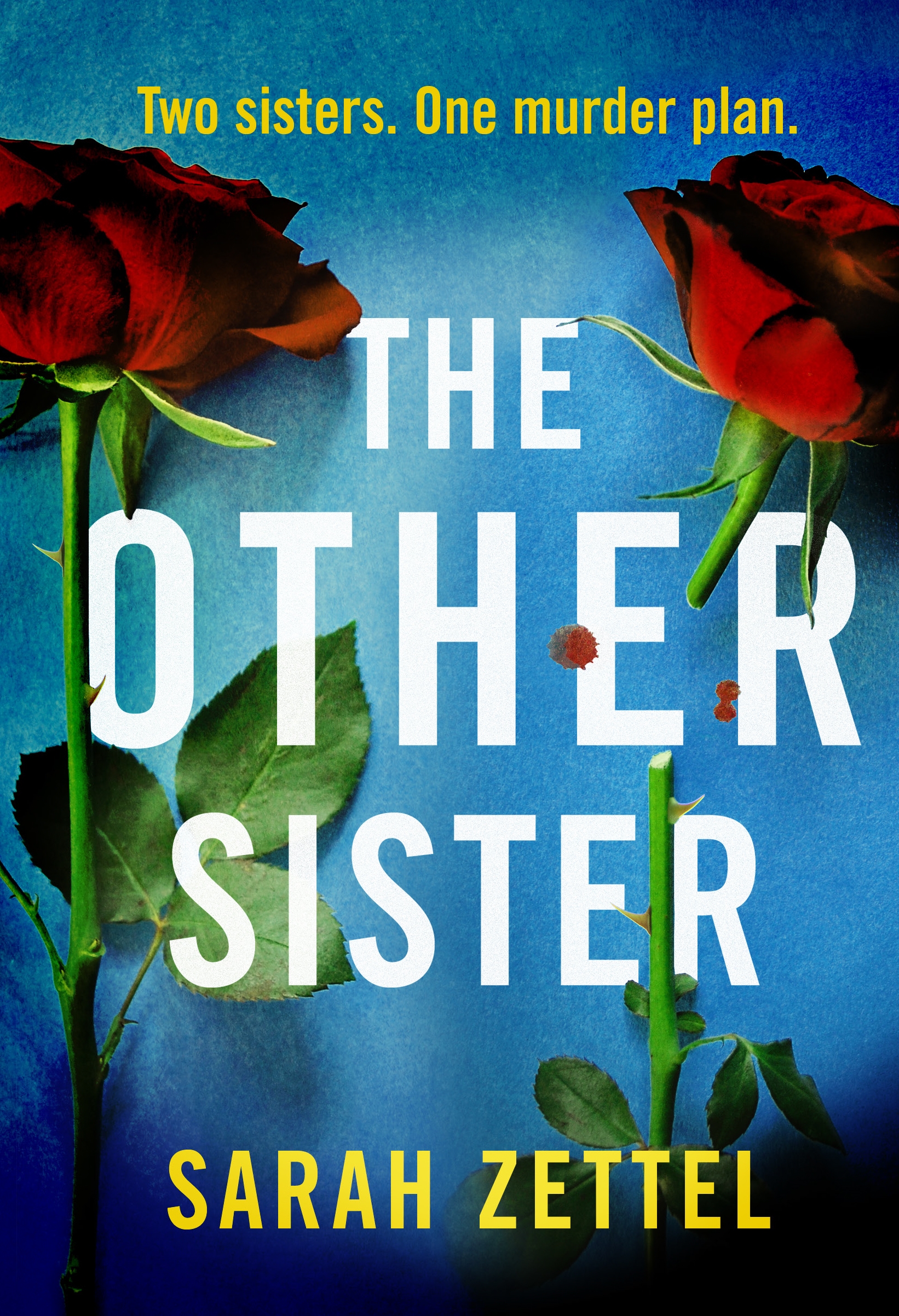

Preview – The Other Sister

“Snowy White, and Rosy Red. Will you beat your lover dead?”

“Snow-White and Rose-Red” from Kinder und Hausmärchen Vol. 2, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, 1812

GERALDINE, PRESENT DAY

MICHIGAN, HEADING NORTH

1.

Twenty-five years ago, I killed my mother.

I tried to kill myself immediately afterwards. Probably that was from remorse, but I have to admit, I’ve never been sure. My suicide attempt, though, didn’t actually work out. You can tell.

I’ve been back before for a couple of weddings, a few births, and the big anniversaries. This time, it’s my nephew Robbie’s high school graduation party. I promised my sister, Marie, that I would not miss it.

Marie has never been above playing the Robbie card to get what she needs from me. She knows I love her son without reservation, and that’s not a feeling I have about many people. So, if she wants something, she’ll say, “Robbie was asking about you.” Or “Robbie’s hoping you’ll be here.” Or she’ll bring out the big guns, like she did this time, when she called to tell me to keep an eye out for the invitation card and the ticket. “You have to promise, Geraldine. Robbie’s counting on you.”

A tight smile forms and pulls at my old scar. Robbie. Prince Charming of the Monroe family’s fairy tale.

I’m one of the world’s experts on the stories of tThe Brothers Grimm and their influence on pop culture. Therefore, I’m qualified to lecture you about the structure of the basic fairy tale arc. Including the fact that in most stories, somebody comes back during the big transitions: weddings, or christenings, or executions. Sometimes it’s that should-be-dead princess returning to claim her castle. Sometimes, it’s the witch or the bad fairy appearing to drop the curse.

I wonder which one I am? My smile broadens. It’s an old, sharp, nasty smile, and the pull deepens. Guess we’ll find out when I get there.

Assuming I don’t lose my nerve.

It’s a tiring drive. Whitestone Harbor, Michigan, is three days away from Alowana, New York, and Lillywell College, where I lecture. You go down through the Allegheny Mountains and across to Buffalo. Over the Peace Bridge. All the way across the flat expanse of Ontario, where you struggle to stay awake and thank God for satellite radio. Over the Ambassador Bridge and through grim, battered Detroit. Then it’s point the wheels north, until the world turns green and the hills roll out in front and bunch up behind.

No matter how many times I do this drive, I need all three days to decide if I’m going through with it. Sometimes the shakes come, and memory blots out the road in front of me. Sometimes, I can’t stop myself from seeing Mom standing in the ruined driveway—her arms thrown wide, so she’s crucified in the headlights. Then, I have to turn around. I have to call Marie and make some lame excuse about a department emergency, or the flu, or the car breaking down. When this happens, Marie always acts like she believes me.

“Are you okay, Geraldine?” she asks. “Do you need help? Do you have enough money?”

“I’m fine,” I tell her, every time.

“Okay then, call if you need anything, all right? Don’t just text. I need to hear you’re okay.”

“I promise, Marie,” I say, and we hang up and I do call, but it’s always to tell her that I went back home and I’m fine, whether it’s the truth or not.

Obviously, I haven’t been caught, or tried, or punished, for my murder. If I was ever even seriously suspected, those suspicions were quickly tidied away. In Whitestone, the Monroe family name is good for that sort of thing. I got asked a few questions in the hospital, and that was that. It was decided that my mother, Stacey Jean Burnovich Monroe, killed herself. Everybody in Whitestone breathed a great sigh of relief. Especially my father’s family.

Perhaps I should say, especially my father.

The two-lane ribbon of black top unspools up and down the achingly familiar hills. Every so often there’s a gravel drive with a little white shack or flat-bed trailer and a hand-painted sign:

STRAWBERRIES

ASPARAGUS

LAST CHANCE

Last chance. The words hover in front of my eyes like a heat mirage. I don’t have to do this. I could turn around. I could break down. Let my phone run out of juice.

I could run away for good this time. All the bridges to the world I thought I’d created for myself outside Whitestone Harbor and Rose House are well and truly burnt. I’ve got my whole life packed up with me. My rusting yellow Subaru is crammed with suitcases of clothes and dishes, and boxes upon boxes of files and academic journals. The parts of my ancient desktop computer ride shotgun on the passenger seat. My sleeping bag and backpack are crammed behind the driver’s seat.

I can go

“Snowy White, and Rosy Red. Will you beat your lover dead?”

“Snow-White and Rose-Red” from Kinder und Hausmärchen Vol. 2, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, 1812

GERALDINE, PRESENT DAY

MICHIGAN, HEADING NORTH

1.

Twenty-five years ago, I killed my mother.

I tried to kill myself immediately afterwards. Probably that was from remorse, but I have to admit, I’ve never been sure. My suicide attempt, though, didn’t actually work out. You can tell.

I’ve been back before for a couple of weddings, a few births, and the big anniversaries. This time, it’s my nephew Robbie’s high school graduation party. I promised my sister, Marie, that I would not miss it.

Marie has never been above playing the Robbie card to get what she needs from me. She knows I love her son without reservation, and that’s not a feeling I have about many people. So, if she wants something, she’ll say, “Robbie was asking about you.” Or “Robbie’s hoping you’ll be here.” Or she’ll bring out the big guns, like she did this time, when she called to tell me to keep an eye out for the invitation card and the ticket. “You have to promise, Geraldine. Robbie’s counting on you.”

A tight smile forms and pulls at my old scar. Robbie. Prince Charming of the Monroe family’s fairy tale.

I’m one of the world’s experts on the stories of tThe Brothers Grimm and their influence on pop culture. Therefore, I’m qualified to lecture you about the structure of the basic fairy tale arc. Including the fact that in most stories, somebody comes back during the big transitions: weddings, or christenings, or executions. Sometimes it’s that should-be-dead princess returning to claim her castle. Sometimes, it’s the witch or the bad fairy appearing to drop the curse.

I wonder which one I am? My smile broadens. It’s an old, sharp, nasty smile, and the pull deepens. Guess we’ll find out when I get there.

Assuming I don’t lose my nerve.

It’s a tiring drive. Whitestone Harbor, Michigan, is three days away from Alowana, New York, and Lillywell College, where I lecture. You go down through the Allegheny Mountains and across to Buffalo. Over the Peace Bridge. All the way across the flat expanse of Ontario, where you struggle to stay awake and thank God for satellite radio. Over the Ambassador Bridge and through grim, battered Detroit. Then it’s point the wheels north, until the world turns green and the hills roll out in front and bunch up behind.

No matter how many times I do this drive, I need all three days to decide if I’m going through with it. Sometimes the shakes come, and memory blots out the road in front of me. Sometimes, I can’t stop myself from seeing Mom standing in the ruined driveway—her arms thrown wide, so she’s crucified in the headlights. Then, I have to turn around. I have to call Marie and make some lame excuse about a department emergency, or the flu, or the car breaking down. When this happens, Marie always acts like she believes me.

“Are you okay, Geraldine?” she asks. “Do you need help? Do you have enough money?”

“I’m fine,” I tell her, every time.

“Okay then, call if you need anything, all right? Don’t just text. I need to hear you’re okay.”

“I promise, Marie,” I say, and we hang up and I do call, but it’s always to tell her that I went back home and I’m fine, whether it’s the truth or not.

Obviously, I haven’t been caught, or tried, or punished, for my murder. If I was ever even seriously suspected, those suspicions were quickly tidied away. In Whitestone, the Monroe family name is good for that sort of thing. I got asked a few questions in the hospital, and that was that. It was decided that my mother, Stacey Jean Burnovich Monroe, killed herself. Everybody in Whitestone breathed a great sigh of relief. Especially my father’s family.

Perhaps I should say, especially my father.

The two-lane ribbon of black top unspools up and down the achingly familiar hills. Every so often there’s a gravel drive with a little white shack or flat-bed trailer and a hand-painted sign:

STRAWBERRIES

ASPARAGUS

LAST CHANCE

Last chance. The words hover in front of my eyes like a heat mirage. I don’t have to do this. I could turn around. I could break down. Let my phone run out of juice.

I could run away for good this time. All the bridges to the world I thought I’d created for myself outside Whitestone Harbor and Rose House are well and truly burnt. I’ve got my whole life packed up with me. My rusting yellow Subaru is crammed with suitcases of clothes and dishes, and boxes upon boxes of files and academic journals. The parts of my ancient desktop computer ride shotgun on the passenger seat. My sleeping bag and backpack are crammed behind the driver’s seat.

I can go anywhere. Marie and I can just keep pretending we don’t know what we know, just like we’ve been doing all our lives.

But then there’s Robbie. And there’s Dad. If I turn around this time, what will I do about Dad?

anywhere. Marie and I can just keep pretending we don’t know what we know, just like we’ve been doing all our lives.

But then there’s Robbie. And there’s Dad. If I turn around this time, what will I do about Dad?